This blog has been written by Rob Hunter from Leicester Ageing Together

I’ve spent most of my professional career engaged with community education. One reason why I see added value in framing this as social pedagogy is the way that the latter works equally across work with individuals (through, for example, the Diamond Model), work with groups (the whole person’s associative groupings) and, potentially at least, with communities in its determination to address structural inequalities and social justice.

Organisations focusing on the individual often underplay the individual’s associative groupings and their lives in community. Organisations focusing on group work often lose sight of both the individual and the wider community. For organisations focusing on community development, the focal task dominates, sometimes at the expense of the individuals and smaller groups involved. For organisations committed to a social pedagogy way of working there is equal weight given to all three dimensions.

Social pedagogues and community educators might both claim strong affinity with community development but I would argue that this needs to be made more explicit in both cases. So, some related thoughts on community and community development.

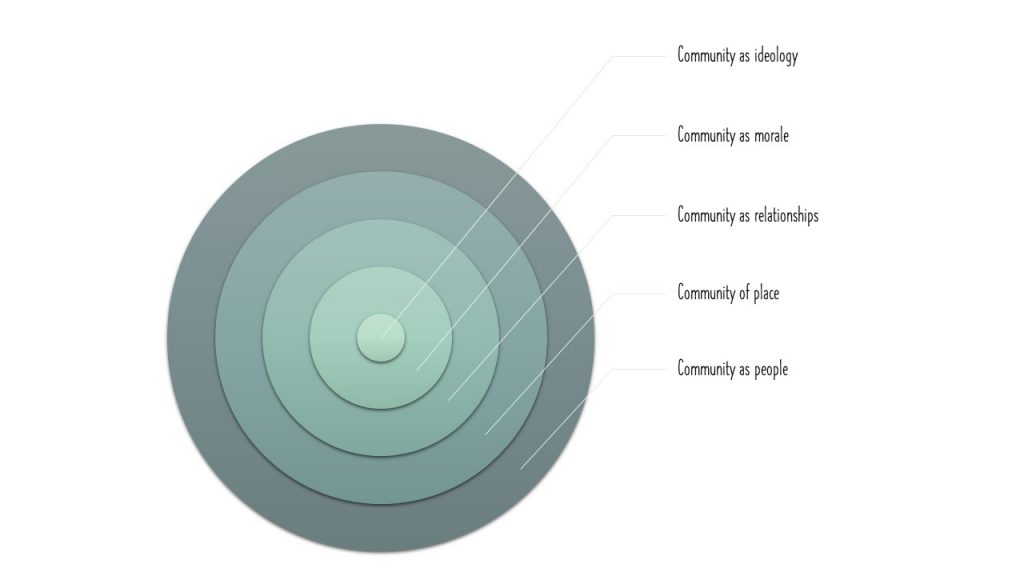

David Clark conceives of community as an archery target. On the outside circle lies ‘community as people’, the generalised language used by politicians and service providers when talking about ‘them out there’. Next circle in, Clark places ‘community of place’ – the bricks and mortar, the roads and shops of neighbourhood. Further in still comes ‘community as activity’, where people are at least doing things together whether in communities of place, in communities of interest, or in communities of identity. One circle further in, Clark places ‘community as relationships’. He quotes Toennies who suggests that human-scale relationships are usually found in the village and seldom in the large organisation, institution or city – but that Clark’s own experience questions this: the village can be an oppressive place to be different in, sometimes riven with cliques, whereas the system of the large organisation can be stewarded to enable its members genuinely to connect with each other and feel part of something bigger.

So far, on his journey towards the Bullseye, Clark suggests there has been a degree of objectivity in the definitions. One can even map relationships. But next circle in, he talks of ‘community as morale’ where the intangible of ‘feelings’ comes into it: ’community spirit’, ‘a sense of community’. He quotes the American sociologist Robert McIver’s 3Ss of community: a place where the individual feels Significant, where they feel physically and psychologically Secure, and where they feel Solidarity. There is a snag here, however. Members of the EDL, white supremacist, ultranationalist organisations and membership of drug gangs also can experience such a feeling of belonging, of community.

And so Clark moves to what he sees as ‘the heart of the matter’: community as ideology. Here community as morale is transformed into a universal value system: where the value of significance, security and solidarity is pursued, not only for those in the community but those living in other communities, in other systems. And he highlights the value of true interdependence. He talks of ‘building community’, of developing a sense of the 3Ss within and between communities, of community development as ‘opening systems up to each other’ with the community development worker as one who works with each of two systems (for example the ‘system’ of young, bored teenagers hanging out on the streets and that of local adults, fearful and hostile to them, calling the police with a dead-handed frequency) to help them listen to each other, stay engaged when the easiest way may be to pull apart, to communicate, to understand each others’ needs, strengths and perspectives and to co-produce solutions – the community worker as Clark’s connecting system.

In that much social pedagogy practice in UK currently is in work with young people and more specifically with looked after children whether in or leaving care, how might these thoughts on community-building be relevant? Three arenas or ‘systems’ come to mind:

- that of the individual young person, perhaps a care leaver, attempting to find out who they are, who they want to become, build their own community around them and connect to other communities as they struggle for independence;

- that, particularly for those working in youth work projects or residential care, between those ‘organisations as systems’ and the systems of the local neighbourhood which can be aggressive or supportive depending on both the relationships fostered between them and whether they see themselves as ‘together’ or ‘other’; and

- that within our own organisations; framing and building them as learning communities, as places in which staff and young people experience a sense of significance, security and solidarity and model that in the organisation’s relationships with others.

Every task, in David Clark’s thinking, has two dimensions: the focal task –i.e. the purpose of whatever we’re doing, be it developing an activities programme or going shopping in the local cash and carry. – and the communal task – the need to take the opportunity of building community as we carry out the focal task. We can carry out any focal task in an instrumental way – or we can use it consciously as an opportunity to strengthen people’s experience of the 3Ss e.g. asking a marginalised member to help you or delegating to a particular subgroup. In our increasingly atomised and divided society it is important for those of us in social work, social care, formal and informal education to help each other and young people both experience community and develop the skills of building it. If we leave it to divisive and destructive groups alone to meet the human need for community and belonging, then we’re leaving those who are most disadvantaged to face a stark choice between isolation or being recruited by those who prey on this human need. We too miss out on the opportunity to release the potential of people acting collaboratively and collectively as a massive social good in itself.

Endnote: I’ve recently been working more with older people in community and residential settings and believe the thinking above is just as relevant to their lives and to this work. I’ve also been introduced to Human Learning Systems thinking and practice and found much rich and complementary thinking here too, in its focus on the whole human being (whether young person or staff) in their associative grouping, on management as learning, and on system stewardship. Perhaps the concepts of community-building and community development have something additional to offer?