Demystifying Social Pedagogy

As a paradigm, social pedagogy is very complex (as other disciplines are too) and indivisibly connected to a given culture (so we can’t fully understand it without understanding the society in which it has emerged). Walter Lorenz, one of the most notable contemporary academics in social pedagogy, suggests that ‘social pedagogy is an important but widely misunderstood member of the social professions’ (Lorenz 2008, p.625). To help readers understand it a little bit better we elaborate on some of the most common misconceptions about what social pedagogy is or isn’t. This list of ‘fake news’ is by no means complete, so if you have more please let us know!

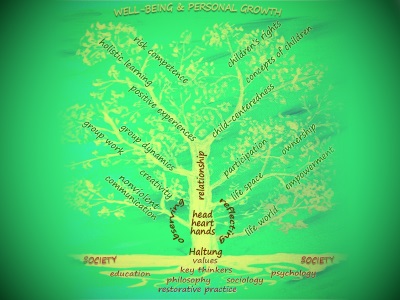

As we have written elsewhere, ‘in understanding social pedagogy it is important to take into consideration that social pedagogy has emerged in many European cultures as an educational response to specific social problems. Intrinsic to it is a “belief that you can decisively influence social circumstances through education” (Hämäläinen, 2003, p. 71) and thereby create a more equal and just society. Mollenhauer (1964) describes it as a “function of society” (p. 21) in that social pedagogy reflects how a given society thinks about children and their upbringing (the “pedagogical”), about the way in which individuals relate to each other and the wider society (the “social”), as well as how it deals with inequality and social exclusion of particular groups (the “social pedagogical”). The function taken on by social pedagogy in asking critical questions as well as finding possible solutions within these areas is socially constructed, thus making it difficult to find one definition that would encapsulate social pedagogy in its complexity without trivialising it.’ (Eichsteller & Holthoff, 2011, pp. 177)Naturally, many other authors have also defined social pedagogy, so there is no shortage of descriptions that would offer a clearer picture of what social pedagogy is about. That may be the impression you can get if you only read the articles about the DfE pilot report by Prof. David Berridge and colleagues (2011) or have heard that Essex is closing their mainstream children’s homes after investing in social pedagogy. But this is not an accurate reflection of the experiences of many organisations. As we explain in our section on the Essex project, the cabinet decision was made for political reasons and not because of the social pedagogical care children can now experience in the homes. If you are wondering about the difference social pedagogy has made, you can read our final report on the Essex project, which includes many practical examples. In any case, people who might think that social pedagogy doesn’t make much of a difference to children’s outcomes are reminded that 10 years of cross-national research by the Thomas Coram Research Unit at the Institute of Education, University of London, tell a very different story. This also becomes very visible when experiencing social pedagogical practice in continental Europe, as is demonstrated in the reports of our English and Scottish participants who spent 2 weeks working alongside pedagogues in Denmark, so there is an increasing amount of evidence that suggests social pedagogy can make a significant difference – it all depends on how well social pedagogy is put into practice though.The research by Berridge and colleagues didn’t aim to evaluate social pedagogy as such – it evaluated a particular approach to implementing social pedagogy and the effect this approach had. It is therefore inaccurate to attribute any ‘failures’ of the Government pilot project to social pedagogy per se, and Berridge et al. actually don’t do this. They emphasise many of the constraining/limiting factors: inexperienced newly qualified social pedagogues being expected to be change agents within a foreign environment, varying levels of support for the social pedagogues in their roles, unclear or exceeded expectations, and organisations not embracing social pedagogy as a whole. This would have had negative implications on any project aiming to create sustainable and substantial change within just 18 months. In this sense, the evaluation findings are unsurprising. As with any other change strategy, the key is for organisations to lead in embracing a new concept – a process that is very complex, demands visionary leadership and, most importantly, takes time. We would echo Berridge et al.’s caution to read too much into a small sample comparison. Data for the baseline and follow-up on young people’s outcomes were collected within less than 7 months on average, which does not provide enough time to have a significant measurable impact. Whilst some organisations may have had the somewhat misguided desire that social pedagogy would prove a quick fix, many others with a better understanding of the complexity of the discipline have been very aware that developing social pedagogy requires an ongoing long-term commitment, which begins with asking some fundamental questions about how we (the organisation and its workforce) conceptualise children, what we want them to experience, how we as professionals want to relate to them and how much of ourselves we bring into these relationships. Finally, if none of this sounds convincing, you can also get in touch directly with organisations that have developed social pedagogy in the UK and ask about their experiences. Here’s a link to the map, which has several of them on it, or alternatively you are very welcome to join a future meeting of the Social Pedagogy Development Network. These are free events and bring together around 100 professionals from a broad range of organisations, many of which have started to explore social pedagogy too. Not at all. Social pedagogues work in many different settings, and their studies enable them to apply theories around learning, well-being, relationships, empowerment, etc. into any context. Social pedagogy is fundamentally based on a humanistic approach and values, so there’s no reason why this wouldn’t apply to life in general. Social pedagogy is in a sense a way of life, a philosophy of how to interact with other human beings. Whilst the main initial interest in social pedagogy in the UK has come from residential child care, over the last few years we’ve seen much broader interest within foster care, adult social care, family support, early years, youth work, education, youth justice and other practice settings. In early 2013, the Fostering Network launched the Head, Heart, Hands demonstration programme that introduces social pedagogy into foster care. We’re hoping to raise more interest in social pedagogy from other services and professionals too. For a better insight into the diversity of social pedagogy in theory and practice, please go to ‘concepts’. You might also find some reading in our resources section that relates social pedagogy to other fields than residential care. Also, there are excellent examples of how pedagogues work in a variety of Danish settings in our Mobility project section. While we don’t want to say that it isn’t, social pedagogy simply isn’t this black-or-white. It’s not something you either do or don’t do. so in many ways this statement misses the point of what social pedagogy is about. It is perhaps more helpful to think of social pedagogy as a spectrum or continuum. It lies within human nature that we have the innate ability to develop and learn. This means we can always move further up the continuum, we can always do something more to do a good job even better, we should always aspire to improve children’s lives. Therefore, the question we should all ask ourselves is: to what extent is what we’re doing social pedagogical? And what can we do to build on it? You might be interested in reading some of the narratives from practitioners on how they have developed social pedagogy, which may give you some ideas on how you could deepen your own understanding of social pedagogy in practice. If you’re still unconvinced, why not come along to the next Social Pedagogy Development Network for a genuine sense of how you could relate your practice to social pedagogy?

First of all, a note of caution on the inflationary use of the term ‘traumatised’ when talking about children in care. Martin Woodhead (1990) comments on the cultural construction of children’s needs, stating that we frequently use pathological terms to describe children and that we need to be conscious of where this is a cultural construction rather than based on facts. Using terms like ‘traumatised’ can become a form of justifying one’s practice that doesn’t aim to fully understand the complexity. This is not to say that children in care haven’t experienced trauma, but that working with the whole child means working with more than just the sum of the child’s traumatic experiences. Social pedagogy is not at all in contradiction with therapeutic child care, although its emphasis is less on the therapeutic and more on the positive aspects of care. As Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2000) note, most of the therapeutic work done by psychologists is actually building on strengths, not treating damage. In a similar fashion, social pedagogy is effective by not focusing on what’s wrong with children but highlighting what’s right with them, thus strengthening their self-esteem and supporting healing. Some children who have had traumatic life experiences will of course require specialist therapeutic support, and it is important for professionals to understand trauma. Practitioners working with traumatized children can use social pedagogy to ensure the children feel safe by having strong supportive relationships and a nurturing environment. None of the principles and aims of social pedagogy would not apply to children with traumas.

Contrary to how social pedagogy is often portrayed in the media, this isn’t really true. There is a longstanding tradition of social pedagogy in continental Europe that is closely linked to welfare traditions, and there are a range of reasons why social pedagogy has, until recently, not developed in the UK as distinctly as in other countries. Yet, there are traditions in the UK that relate to social pedagogy, and various professionals have begun to explore these, most notably Smith (2009) and Smith & Whyte (2008). This means that there is a lot to build social pedagogy on and from which to develop a UK tradition of social pedagogy. And it would not be pedagogic to dismiss or erase this! If you would like to find out more on the history of social pedagogy, please look at this section.

Although we don’t think that financial arguments should take priority over children’s well-being, even in economic terms social pedagogy makes sense. Granted, professionals who are more highly qualified will cost more than those who aren’t, but staff ratios in German children’s homes are lower, for example, as there is more group work and less one-to-one. Also, high quality care makes lots of financial sense where paired with a social pedagogic system that emphasises prevention, stability and careful transitions. The most compelling economic analysis of the cost of social pedagogy has been undertaken by the external evaluation team of the Head, Heart, Hands demonstration programme. The independent researchers from Loughborough University used their widely respected cost calculator for children’s services to explore costs saved and costs avoided through investment in social pedagogy within demonstration sites. The report, which is a preview of further substantial cost analysis as part of the final evaluation in late 2016, is available here. Similar reasons are also demonstrated in the Demos report ‘In Loco Parentis’, which outlined just how much money could be saved by having a wide range of service options that support families before taking a child into care is the only option, and emphasise stable placements that provide the best support with as little disruption in the family’s life as possible. Demos have even done the maths and suggest that this could save as much as £30,000 annually per child in the short term and even more in the long run, given that we’re talking about giving children a much better chance to succeed in life. In addition the New Economics Foundation demonstrated in their report ‘A False Economy’ that ‘for every additional pound invested in higher-quality residential care, between £4 and £6.10 worth of additional social value is generated’. It seems reasonable to understand too: if we give children in care a chance to have a positive future, do well in education and find a good job, society will benefit from the investment during their (tax-paying) adulthood. Where we fail children in care and send them off without formal education, without good job prospects, and without caring about their well-being, they are much more likely to depend on social welfare benefits, end up in prison, or with a track record of ill health, all of which costs society money. It shows that doing the right thing is also much more financially viable in the long run. This is a very interesting misconception, mainly because of how ‘not having any rules’ is understood. A lot of social pedagogues would say they don’t have rules, but they have values and norms instead. Where breaking rules lead to sanctions, breaking with values and norms on the other hand leads to consequences. Importantly, this is not just about semantics, it is about a fundamental difference in attitude. Values and norms count for everyone alike and are communicated in interaction – they don’t become transparent by being written on the wall, but through the culture, in the lifespace. This means they are intrinsic in that social pedagogues role-model them and aim to convey and negotiate them with the children. Rules are often just written down, but the motivation to follow them is extrinsic, that means caused by fear of sanctions or hope of rewards rather than by understanding and sharing their value.Social pedagogues do set boundaries as well, but these are not set in stone. Neither are they there in order to exercise power or control. Rather, boundaries are set to give children a sense of feeling safe and secure, where they can trust the adults to make good decisions for their well-being. Another interesting thought on this comes from one participant of ours, who explained social pedagogy as not saying ‘no’ to children all the time, but thinking together with them about what would need to happen to make something a ‘yes’: you might not let them take out their bikes before they have done their home work, but instead of saying ‘no’ you engage in a dialogue to find a solution together with them. As G. B. Shaw once said about communication, ‘The problem with communication … is the illusion that it has been accomplished’. The same could be said about implementing social pedagogy, because it is an ongoing process of developing at a professional, personal and practical level. Because the world around us changes, the children and young people change, our teams change, and we ourselves change, so must social pedagogic practice.