The concept of Multiple Intelligences was developed by Howard Gardner, a professor of education at Harvard University, and first published in his book Frames of Mind (1983). It quickly became established as an important model explaining the different ways in which we learn, think, understand and act. Gardner’s main idea is that intelligence has many forms, that we’re all intelligent in different ways. Therefore, the common assumption that some people are highly intelligent whilst others are not very intelligent, and that intelligence can be assessed through measures such as the IQ test, is both deeply flawed and unhelpful. It prevents us from understanding intelligence more broadly and from creating meaningful learning opportunities. Sadly, it also means that many children and adults feel judged as ‘stupid’ or ‘bad’ for not being intelligent in the narrow way in which we traditionally conceptualise intelligence.

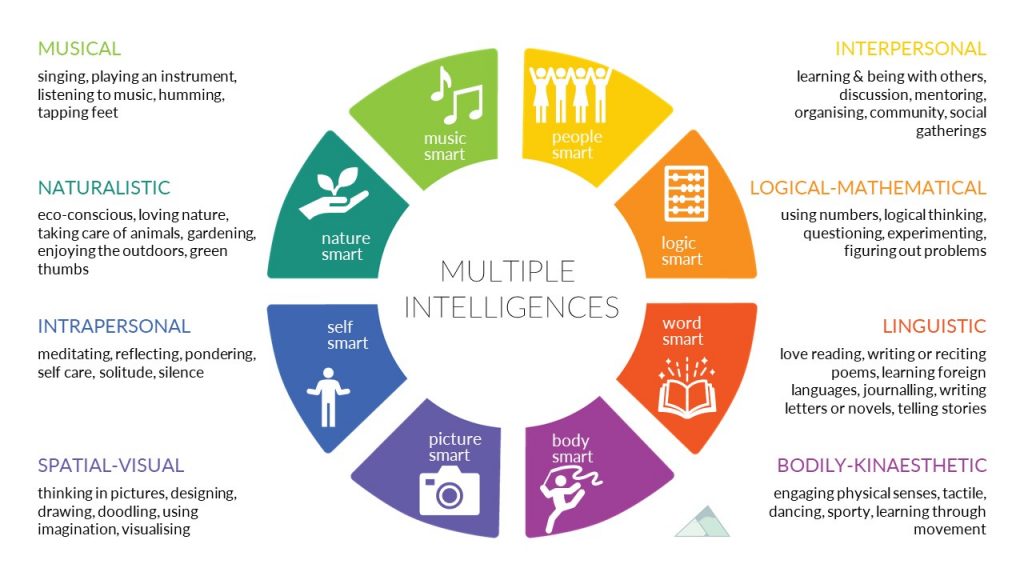

Gardner argues that each person has a unique blend of multiple intelligences, not just one type or level of intelligence. He originally identified seven different intelligences (see image): logical-mathematical, linguistic, spatial-visual, musical, bodily-kinaesthetic, intrapersonal and interpersonal. The types of intelligence that we possess both affect how we perceive the world (what we might be most in tune with, which senses we might use) and how we prefer to learn (how we have come to understand the world). For instance, a child with a stronger bodily-kinaesthetic intelligence is keen on tactile experiences, might like to touch all the ingredients used in a cake recipe and might most meaningfully learn about aerodynamics with a parachute strapped on so as to physically experience the forces at play. A child with stronger musical intelligence might be more tuned into the sounds around them and might learn a poem much better by turning it into a song.

Gardner suggests that most of us are strong in three types of intelligence, which come most naturally to us. They are likely to influence what we enjoy doing (e.g. playing chess – logical-mathematical, dancing –bodily-kinaesthetic, socialising with friends – interpersonal) as well as how we learn. It is important to recognise that, according to Gardner, all intelligences have equal value. None is better or more desirable or more likely to cause happiness. However, we need to understand our own blend of intelligences and use this to our advantage, because our intelligences provide important clues about how we best learn, what our preferred learning styles are and how we can develop our strengths as well as our weaknesses.

Perhaps the most obvious yet commonly ignored implication of multiple intelligences is that, as human beings, we learn far better and far more effectively if we use our strengths. We’ll feel better, more relaxed and more confident as a result, whereas the pressure of possible failure and being forced to act and think unnaturally cause stress and have a corrosive effect on our learning. Developing our strengths will make us more responsive to learning experiences that help us develop our weaknesses too. For instance, a child who is interpersonally intelligent might find it a lot easier to develop a weakness in linguistic intelligence and learn French by meeting up with children who speak French or improvise a role play with their friends in French than by reading a book in French – which might be a much better way for a child with strong intrapersonal and linguistic intelligence to learn the language. Neither of these ways are superior and both children could end up doing equally well in French if given the opportunity to learn it in the ways they learn best.

As professionals engaged in learning settings (both formal and informal, with children or adults), we therefore have particular responsibility to ensure that learning opportunities reflect multiple intelligences and the diverse ways in which people learn effectively. Gardner’s model provides an excellent framework, which has been taken up by many schools and other educational settings, sometimes translated into different areas of being smart (see above). Some schools have gone so far as to design the school environment accordingly, with cozy quiet corners for intrapersonal learners (‘self smart’ students), social spaces for groups of interpersonal learners, areas for bodily-kinaesthetic learners to be physically active and zones where naturalistic learners can engage with pets or tend to flowers. Even small ways of encouragement can make a big difference: a ‘body smart’ child constantly fiddling with a pen might find it easier to concentrate if they can shape a lump of play-do; a ‘picture smart’ child might just need somewhere to doodle.

Since Gardner first introduced the 7 multiple intelligences, he has further developed the model, which now commonly includes naturalist intelligence as an eighth form of intelligence to describe people who are very in tune with their natural environment, enjoy being outdoors, love gardening or caring for a pet. Gardner has also considered further intelligences, particularly spiritual and moral intelligence, but these are much more complex and therefore also more difficult to measure and evidence.

Finally, as human beings we cannot possibly be strong in all multiple intelligences. In life we need people who collectively are good at different things. A well-balanced world, and well-balanced organisations and teams, are necessarily comprised of people who possess different mixtures of intelligences. This gives the group a fuller collective capability than a group of identically able specialists. We can thus greatly benefit by actively and non-judgmentally engaging with people who are different to us.